Saint Vincent de Paul: the apostolic life

When Vincent de Paul was born (1581-1660), he was one of the many peasants of his time. He didn’t have blue blood in his veins! His was a culture that did not allow him to write great works, every career was barred to him. Yet, while many were asking the why of things, he overturned the existing values, wondering: “why not?” Why can’t things change , innovate, improve? This was the question of courage, of the Mission, of the charism of charity.

With his action and his sensitivity he changed the way things are understand, so much so that after him the Church and the world were no longer the same. He invented a new role for the woman, placing her at the centre of the life of humanity with its needs and hopes. He did not invent charity, but discovered it within the Church and placed it at the top of the interests of the world.

In him there isn’t only the “saint”. There is also a century, a people, a landscape. There is a lifetime. There is a church. There is God.

We are in 17th century France, characterized by wars and political struggles, famine and epidemics, appalling poverty of populations, especially in the countryside. The French State was not only unconcerned, but its politics were aimed at “elevating the name of the King over foreign Nations”. And this led the socio-economic situation to tragic levels: many beggars, tramps, abandoned children; begging in the 17th century is a worrying and disturbing problem. Infant mortality grows: 50% of children die before one year of life. The situation in hospitals is terrible, where the poor and the tramps are locked up, considered to be vehicles of diseases, disorders and immorality. The treatment reserved for prisoners is inhuman. The French peasant, living in poverty suffers hunger, is oppressed by all kinds of burdens and tithes, conditions that provoke furious riots in the country. Productivity is low due to backward agricultural techniques, to bad weather (years of freezes, floods, droughts), to raids of bandits, the lodging and presence of troops during the thirty years’ war, which resulted in famines that also produced epidemics and plagues.

Vincent summarized this distressing reality in the famous phrase: “The poor starve to death and damn themselves”. Moreover, at that time, the poor person was not considered as the Christ to be clothed (St. Martin) or to be helped to ford the river of life (St. Christopher): the poor man represented — according to scholars – the “great fear” of the century.

At the same time, the French Church was shaken by heresy, rejected due to the opulence and the worldliness of bishops and prelates, for the decadence of fervour and the scandals in the cloistered monasteries and for the ignorance and the immorality of priests. Some enlightened Bishop had tried to create groups of consecrated virgins dedicated to the poor, the sick, orphans, illiterates. But he hopelessly collided with the mentality of the time: it was unthinkable for a nun to be outside the security of the enclosure, deemed necessary to protect the female fragility.

Rome: Mosaic of the chapel of the General House:

Saint Vincent and saint Jeanne-Antide

Rome: General House

Borgaro: in the chapel of the sisters of Charity

A little at a time, and amidst a thousand difficulties, Vincent realized that the Lord called him for a mission in all fields and, at the end of his long life he was recognized by the Church and the society of the time as

- EVANGELIZER of the COUNTRYSIDE

- FATHER OF THE POOR

- FORMATOR of the CLERGY

- INNOVATOR OF FEMALE RELIGIOUS LIFE

To meet the needs of evangelizing the countryside, St. Vincent founded the Congregation of the Priests of the Mission, a group of traveling priests dedicated completely to an extraordinary style of proclamation, capable of inspiring a genuine Christian revival. It partly continued in the great work of the preachers of the late Middle Ages, but the differences introduced by Vincent were significant: the missions had a more ecclesiastic character, in the sense that they started from a missio canonica, that is, they were “sent” by the parish. They were not extraordinary “envoys”. They had a more systematic character and followed a style of evangelization and renewal modeled on the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises. It underlined the personal encounter with God through general confession and communion, giving importance to catechetical instruction, for which Vincent had a true passion. The ideal aim was to bring all Christians “to live in holiness”: the Missions, for Vincent, represented the main ministry.

The activity of the first missionaries was tireless. In the first six years they preached about 140 missions: keeping in mind that they were only seven and went on a mission in groups of two or three, it meant that they were engaged nearly three hundred days per year. They were the first who managed to preach the missions according to three principles desired by the Council of Trent: “educate, convert, be understood”.

The Missions gave birth to Spiritual Retreats and prayer groups such as the Associations of Perpetual Adoration, so that at some point the missionary left the place to the parish priest and the mission became a simple Pastoral Ministry.

Being close to the priests of the rural parishes, he realized the state of ignorance of the French clergy: it was enough for a young man of goodwill to be ordained after apprenticeship with a parish priest who knew little more than himself. The consequences of this limited formation were severe: not many knew the formulas of the sacraments, there were those who were confused, not to mention those who celebrated a “summary of the mass“. Until that time, in France, the Council of Trent had remained a dead letter regarding the openness of the seminaries. Vincent took hold of this situation and founded seminaries in many dioceses of France under the direction of some priests of the Mission.

He started with 10 days retreats preached by the Fathers of the Mission, for those who were about to be ordained, first in the Diocese of Paris and later in other dioceses. For ongoing formation, there were the lectures on Tuesdays. The Seminaries were a natural continuation of the retreats.

As he moved along the French countryside, he assumed the responsibility for the tragic situation of the people thrown into despair, causing the number of beggars and refugees to increase: “the poor who do not know where to go or what to do, who are suffering and multiply daily, are my burden and my pain“. When faced with the state of extreme need of a poor, abandoned family, Vincent had an extraordinary intuition: he called some noble ladies to form a stable group in the parish for the relief of the poor, the Ladies of Charity.

This partnership of laity contained within itself the germ of two exceptional novelty in the exercise of Christian charity: the Vincentian lay movement (Volunteering, Conferences of St. Vincent) and the Company of the Daughters of Charity. Until that time, the Church practiced only almsgiving and charity: by individuals and by the nobility. But almsgiving was sporadic and disorganized, entrusted to the good will of individuals and charity was donated by the rich, nobles, aristocrats … With Vincent a charity that is structured, organized, consistent and attentive is born.

St Vincent started an organized lay parish group with a communitarian spirit at the service of the poor. This group gave birth to the Daughters of Charity that was also a key moment experience for the history of female religious life in the Church: where Saint Angela Merici, St. Francis de Sales and others failed, St. Vincent and St. Louise de Marillac succeeded. They achieved a genuine re-foundation of female community life, creating a new style of woman’s presence in the Church and in society: the Daughters of Charity were recognized as the most daring Institute of the seventeenth century. While having great respect for the traditional cloistered convents, Vincent realized that if his Daughters were to be recognized as a new religious order, the grate was a necessity for them, essential to safeguard women who had no husband’s protection. Therefore Solemn Profession was not required of the Daughters of Charity (as this would have meant for them enclosure and, with it the end of the service to the poor). They were also neither obliged to wear a special habit nor to live in places separated from ordinary people.

Among the key points of novelty was the rejection of the alleged biological law that considered the woman as weak and inconsistent and therefore incapable of direct intervention in social life. For the first time, St Vincent had reacted to the custom of the time where families had to provide very high dowries for their daughters to enter a convent. The Daughter of Charity, instead, to be able to understand fully the needs of the poor, should be of modest origins, both on a cultural and social level and, in any case, she was called to assimilate the solid virtues of hard work, of being trained in a spirit of tirelessness, in the obedience and poverty of the rural young women, of the “good daughters of the fields”. If a noble young woman joined the Daughters of Charity, she would not assume a privileged position but had to conform to the poor style of the Institute.

Vincent is aware of the novelty and difference of his Institute as compared to other female institutions of the time: If the Augustinian sisters served the sick in the Parisian hospital, Hôtel Dieu, and the Hospitallars of Charity of Notre-Dame in the hospital Place Royal in Paris, the Daughters of Charity go to look for them in their homes and assist those who would have died without aid, not daring to ask for it. Assisting the foundlings, the prisoners and the elderly, “the poor mad people”, the soldiers in military camps, the wounded on the battlefield, they perform a “service” that was not done by any other religious community.

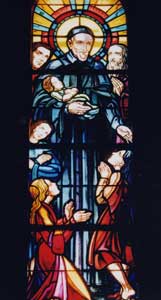

La Roche/Foron (France):

stained glass in the community chapel

La Roche/Foron (France):

stained glass (detail)

Besançon: in the community chapel ,

131 grande rue

The religious ideal of the Daughters of Charity was stated at the beginning of the Rules: “The main purpose for which God has called and united you is to honour our Lord Jesus Christ as the source and model of every form of charity, serving him bodily and spiritually in the person of the poor, the sick, prisoners or other types, who out of shame do not dare manifest their needs”. The common Rules and the special Rules for the sisters working in parishes and in villages, for the sisters teaching in the schools and for those working in the hospitals and in the prisons were built around the identification of Jesus Christ in the person of the poor. They were a set of detailed rules, and at the same time rich in humanity, that would respond to the multiplicity of services and to the vastness of requests. At the first place were the poor, “to serve with great sweetness and cordiality, understanding their pain, listening to their complaints as a good mother should do, because the Daughters of Charity are intended to represent God’s goodness toward the poor. They represent the person of our Lord, who said: «all that you do to the least of my brothers and sisters, is considered done to me»”. In the fire of a charity that was active and industrious, Vincent de Paul was able to achieve the “adherence to Christ” through “the adherence to the poor”. The service for the poor was considered so much a priority that in many cases the Daughters of Charity were to leave the spiritual practices laid down by the rules to assist the destitute.

For this, the Vincentians were called to re-interpret all the classic elements of religious life (common life, chastity, obedience, poverty, prayer and silence, distance from worldliness) in an absolutely new form that responded to the needs of the times. Search for the face of God, life in common, obedience, chastity, poverty, are not complete in themselves, but constitute the elements of a proactive presence of evangelization and charity among men and women: evangelical experience, therefore, is accomplished in the solitude of the cloister as well as in the service to one’s neighbour.

Vincent de Paul had to make every possible effort to persuade the Church authorities that in the case of the Daughters of Charity they were not nuns, but young girls united in a community, free to roam the streets of the city, to enter the homes of the poor, the hospices and the prisons. They became, therefore, the model of new charitable religious communities of women: the sisters did not wear any special habit, they lived in buildings called “houses” and not convents; the time of preparation for religious life was called “seminary” and not the novitiate and their professed vows were temporary: they were valid only for the time of stay in the Company.

Their service to the poor quickly assumes unthinkable and immense attention, in an era that experienced the fear of the poor and indifference toward them, if not also rejection of childhood: indigent patients at home and in hospitals, basic education in rural areas, assistance to foundlings, orphans, galley slaves, beggars, abandoned old people, people with mental disability, soldiers on the battlefield were all places of action of the Daughters of St. Vincent since the origins of the Company.

Vincent calls the poor “our lords and masters”: and the lord in the 17th century was surrounded by a sacred aura, which demands respect and veneration: for Vincent, this meant the complete reversal of values where the last became the first, “the lords and masters” to whom one owes respect and devotion. His was a spiritual perspective, steeped in history, founded on solid virtue, distrustful of religious sentimentality and of exceptional mystical phenomena that meant self-centredness and a refuge to one’s individualism which was so in vogue at that time: “in this you will recognize if you are true Daughters of Charity — he often reminded his sisters — with no ambition or conceit: if you do not think of yourselves as being more than you are or better than others, both physically and morally, because of one’s family or because of riches, nor for the virtues, because this would be the most dangerous ambition” (5 Jan 1643).

In a famous paragraph of the Rule of the Daughters of St. Vincent is summed up what later became also the heritage of the community founded by Jeanne-Antide. In her Rule of 1802 these same words are recalled, when one traces the identity of the Sisters of Charity of Besançon:

“As they usually have the house of the sick as their convent;

rented houses as their cells;

the parish church as their chapel,

the streets of the city and the hospital wards as their cloister;

obedience as their enclosure;

fear of God as their grate,

and holy modesty for their veil,

they should, by virtue of this, lead a religious life

as if they had professed their life in a Religious Order”

The traditional cloister, founded on an experience of isolation from the world, lost its exclusive character of the culmination of the “state of perfection” in the belief – continually reiterated in his famous Conferences and in his writings – that contemplation, common life, ascetic commitment, do not end in themselves, but constituted a prerequisite for effective action among people. One of the main fruits of this new apostolic vision, the Rule of the Daughters of Charity, with its typical spiritual profile and its openness on the world of the poor, was therefore a model-guide for many other types of religious communities which, in turn, were inspired to the “Vincentian” tradition.